TL;DR: I built a clean, customizable logging utility in Python and learned about programming architecture along the way.

The Problem

I needed a logging utility that was flexible enough for multiple projects but was not overly complicated for my data engineering pipelines.

The Solution

Build an importable setup_logging function that creates an app-level logging object and attaches a console handler and a file handler. This gives me clear, real-time visibility during development and a persistent error trail for debugging and refactoring.

Architectural Decisions

I wrestled with several architectural decisions while building this API, which helped me get a feeling for the considerations that go into building a robust and flexible program.

- The most important question: what did I need the logs for? I determined that for my current purposes, I wanted to see runtime execution, warnings and errors in the console, and keep a persistent file that captures all warnings and errors for traceability.

- Secondly, I needed to balance flexibility with simplicity in considering which functions I needed to be customizable. I decided that the module cold set the log format and that I didn't need the ability to add child logs or additional handlers for now. But I programmed in the ability to determine the levels for the logging object and both handlers. And of course, I need to be able to assign the log name and log file name locally.

- Finally, I needed to decide on the package's call flow (see below).

Call Flow

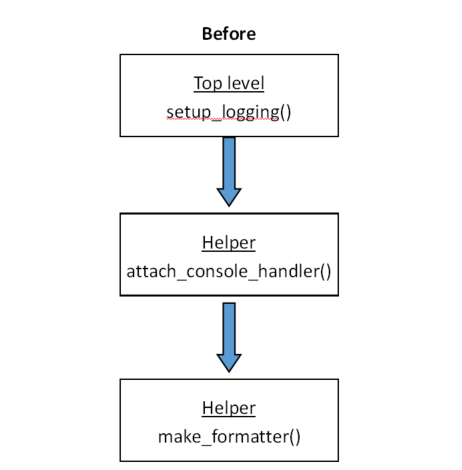

In my first iteration, decisions were split between setup_logging (top-level function), and attach_console_handler and make_formatter (helper functions).

The call flow was linear:setup_logging -> attach_console_handler -> make_formatter

This worked fine as long as my top-level function was simple and rigid. But as I added customization, I knew the structure would get tangled quickly.

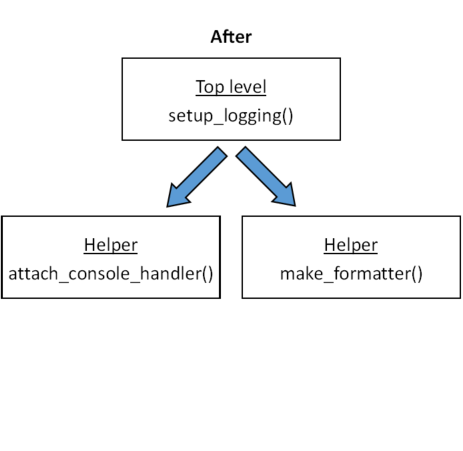

So I refactored by placing all the decision-making in setup_logging and designing my helper functions as simple plumbing. This separation of concerns gives me a clear structure, fewer hidden dependencies, and a logging setup that scales elegantly.

How the Call Flow Changed

Measuring Stick Moments

While building and testing this API, I had several moments that allowed me to see how far I have come.

- I implemented the full utility in a single focused session — a big leap from where I was a few months ago.

- I conceptualized two different structures for how helper functions interact with the top-level function, and saw the pros and cons of each. It was not long ago that I would write one giant function containing all the logic.

- I installed the API as an editable package (

pip install -e), which let me import it into a test script immediately. - I followed the tracebacks across multiple scripts and fixed bugs.

Clarified pytest

I also clarified when to use pytest (and ruff). The mental rule I landed on — build pytests when:

- the code has been used in real-life applications and has stabilized.

- errors are difficult to see and/or can occur silently.

- errors are costly (i.e. they affect data in the pipeline).

- the application produces a lot of edge cases.

- the cost of being wrong is greater than the cost of writing the tests.

For example, ETL transformations or CSV parsing functions benefit from tests because mistakes are silent and expensive.

Takeaway

Good design isn't about adding features — it's about putting decisions in the right place. By assigning all policy-level decisions to setup_logging and designing helpers to simply execute those choices, I built a logging utility that's both simple today and scalable tomorrow. This was a small utility, but it taught me a big architectural lesson.

Related Posts

tags: #general-programming, #Python, #logging,#tools-and-languages, #applied-learning